Balamos

In cinema, there is this possibility of what is to come, of a new awakening. There is a possibility of a future existence.

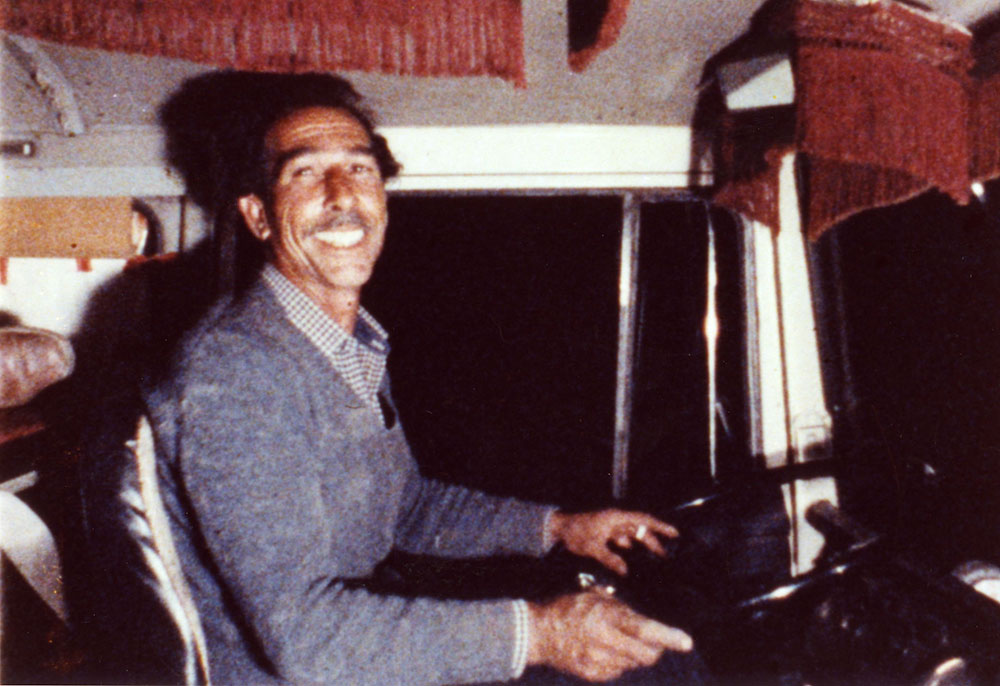

Stavros Tornes is one of the forgotten prophets of cinema, poète maudit steeped in the land of myth and tragedy, companion of all the outcasts of the post-industrial society, of all the vagabonds wandering amid the wreckage of Empire. Always choosing the enchantment of the world, in all its exuberance and intemperance, in the face of the disenchantment of the social, tinted by memories of occupation, civil war and dictatorship. In the handful of films he made with his “alter ego”, Charlotte van Gelder, there is no rift between the real and the surreal; reality and the imaginary flow into each other as if the concrete world were inhabited by ancient animistic forces. In the course of seemingly aimless voyages through space and time, adrift in a dérive through foreign landscapes, we are offered the unexpected wonder of another humanity in its many figures: the return to the origins, the descent to the netherworld, the arrival in the promised land. “Homer operating the camera, Heraclitus recording the sound”, as film critic Louis Skorecki once wrote. A cinema before cinema: primordial, unattainable, mythical. A cinema that makes us whisper, in complete bewilderment, “Where am I?” Not for fear of being lost, but because of the revelation of being in a deep sleep, suddenly awakening, and not knowing what estranged world we have woken up to.