07: Shorts: E. Owens / F. Woods / C. Billops & J. Hatch

In the presence of Fronza Woods.

Courtisane is een platform voor film en audiovisuele kunsten. In de vorm van een jaarlijks festival, filmvertoningen, gesprekken en publicaties onderzoeken we de relaties tussen beeld en wereld, esthetiek en politiek, experiment en engagement.

Courtisane is a platform for film and audiovisual arts. Through a yearly festival, film screenings, talks and publications, we research the relations between image and world, aesthetics and politics, experiment and engagement.

COURTISANE FESTIVAL 2026: 1-5 April

In the presence of Fronza Woods.

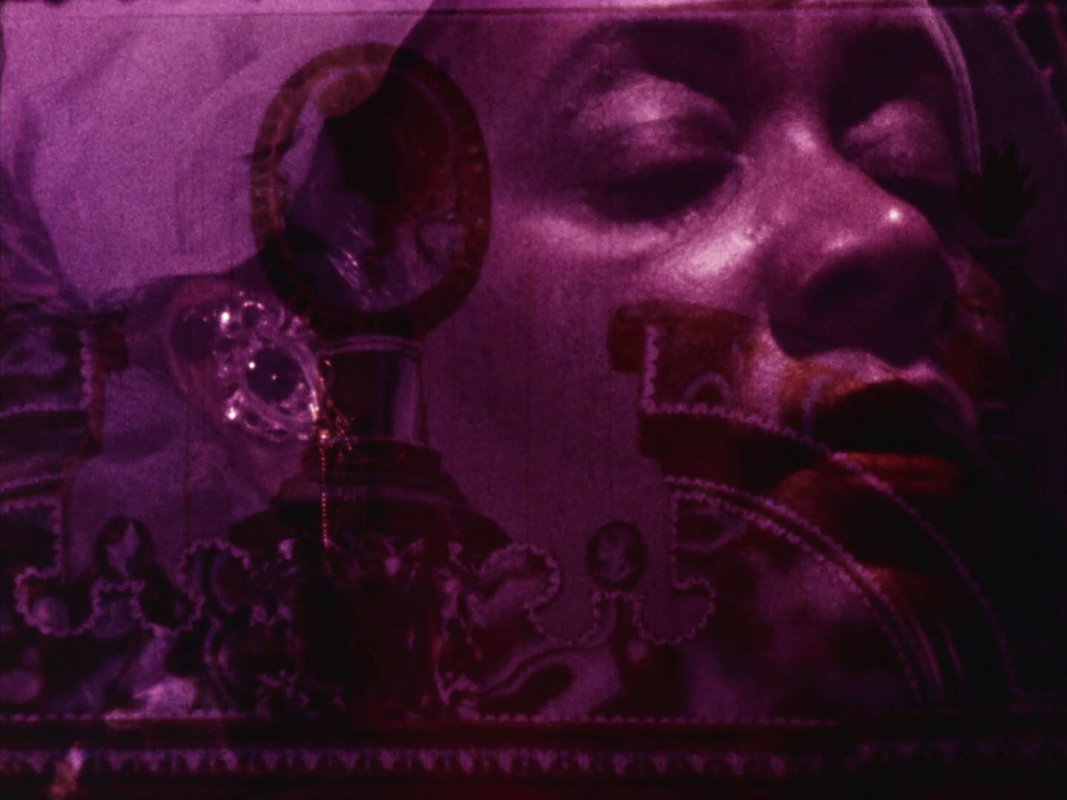

In the mid 1960s, Edward Owens (1949-2009) was an African-American teenager attending the Art Institute of Chicago when Gregory Markopoulos arrived to found the school’s film program. Owens, who was then studying painting and sculpture, had already been making 8mm movies for a few years; impressed by the maturity of his work, Markopoulos encouraged him to move to New York. Over the next four years, Owens created a cluster of films that display an increasing mastery of form, inspired by Markopoulos’s style but transformed into something purely his own. Remembrance: A Portrait Study and Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts were both shot in Chicago, and bring his formidable repertoire of techniques to bear upon nonfictional subject matter: his own family and their circle. Remembrance pictures his mother, Mildered Owens, and her friends Irene Collins and Nettie Thomas. The women are shown drinking, smoking, and hanging out, their faces lit like 17th-century paintings, set to a soundtrack of pop songs. Originally titled Mildered Owens: Toward Fiction, the achingly silent Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts focuses more directly on his mother, setting her regal depiction amidst delicate pulses of editing and oblique superimpositions, evoking the gap between the homebound realities of life and desires for far-off luxury and refinement. In spite of praise by the likes of Parker Tyler and Jonas Mekas, Owens’s filmmaking career tragically ended when he was only twenty years old. (Ed Halter)

“Edward Owens may well be one of the few for whom ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ need have no significance whatsoever: true to his own native talents, with grim determination uncanny, whether the mind in the arts is for or against beauty or its opposite twin, chaos. So that with each subsequent struggle to complete a film he will leave us breathless with anticipation for his next work.” — Gregory Markopoulos

New digital preservations by The Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

“A montage of still and moving images, mixing and alternating black people and white people, fantasy and reality, a presidential suite and a mother’s kitchen: a sensitive, poetic evocation in the manner of the filmmaker’s Remembrance. Brilliantly colored and nostalgic, it comprises a magical transformation of painterly collage and still photographic sensibility into filmic time and space.” (Charles Boultenhouse)

Fronza Woods was born, raised and educated in Detroit. She began her professional life as a junior copywriter at a small Detroit advertising agency. In 1967, she moved to New York, where she continued to work in advertising. Then, at a time when television was opening up to people of colour, she went to work for ABC news, before learning to craft her own films at the Women’s Interart Center under the aegis of Ellen Hovde and Muffie Meyer. Killing Time, an offbeat, wryly humorous look at the dilemma of a suicidal woman unable to find the right outfit to die in, examines the personal habits, socialization, and complexities of life that keep us going. When the film recently screened, Richard Brody wrote in The New Yorker: “very simply, one of the best short films that I’ve ever seen,” comparing it favorably to Chantal Akerman’s first film Saute Ma Ville. In Fannie’s Film, a 65-year-old cleaning woman for a professional dancers’ exercise studio performs her job while telling us in voiceover about her life, hopes, goals, and feelings. The first in an unaccomplished series of portraits dedicated to “invisible women”, Fannie’s Film offers “a brutal, brilliant allegory for women and film” (Manohla Dargis, The New York Times). In addition to making her own films, Woods has worked as camerawoman on numerous independent films, was assistant sound engineer on John Sayles’ The Brother from Another Planet (1984) and a cast member in Yvonne Rainer’s The Man Who Envied Women (1985), and taught basic filmmaking at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, where she also created and curated an outreach film programme for the city’s black community. She now resides in the southwest of France.

“I like films about real people. I am inspired by almost everything but especially by struggle. I am interested in people who take on a challenge, no matter how great or small, and come to terms with it. What inspires me are people who don’t sit on life’s rump but have the courage, energy, and audacity not only to grab it by the horns, but to steer it as well.” — Fronza Woods

English spoken, no subtitles

Prints courtesy of the Academy Film Archive and Women Make Films.

After studying sculpture on the west coast, Camille Billops moved to New York, where she earned a master’s of fine arts degree from the City College in 1973. Together with her husband James Hatch, she subsequently founded the Hatch-Billops Collection, an extensive archive of African American cultural history. They began their career in filmmaking in the early 1980s with Suzanne, Suzanne, the first in a series of films dealing with Billops’s family. The film profiles her niece, Suzanne Browning, as she struggles to come to terms with the legacy of her abusive, now-deceased father, and her escape into heroin addiction as a respite. Suzanne is compelled to understand her father’s violence and her mother’s passive complicity, who suffered at her husband’s hands as well, as the keys to her own selfdestruction. After years of silence, Suzanne and her mother are finally able to share their painful experiences with each other in an intensely moving moment of truth. Emotionally raw and wrenching, Camille Billops autobiographical approach has been described as “a means to a new black documentary style” (B. Ruby Rich, Sight & Sound).

“I’ve always liked Camille Billops’s films. Suzanne Suzanne is one of my favourite films, because more than any other films by independent black filmmakers, she really compels people to think about the contradictions and complexities that beset people. We’re not used to women artists of any race exerting that kind of relationship to art.” — Bell Hooks

English spoken, no subtitles

Copy courtesy of The New York Public Library and Third World Newsreel.