Courtisane festival 2017

- Ghent

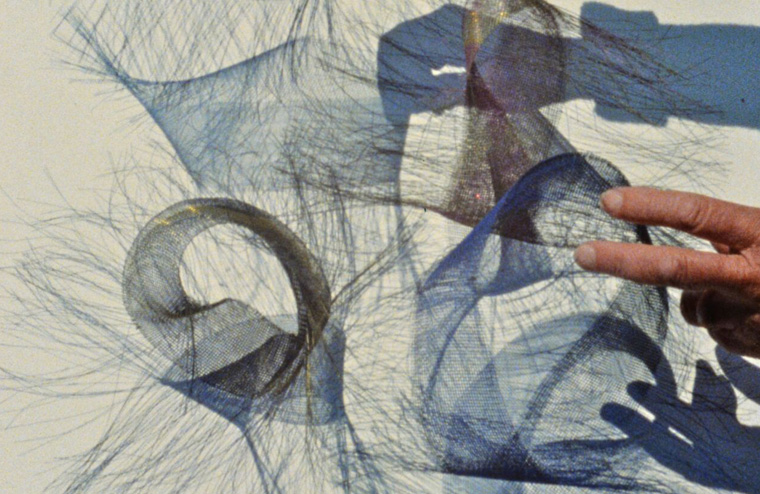

One of the recent film works that has touched us the most might also be one of the least conventional. Not only is this film completely devoid of a scripted narrative or overtly presented rhetorical argument, it also shows no bodies or faces that could arouse empathy or identification. The only ‘action’ we get to see is performed by sunlight and breezes of wind. This was, in fact, not meant to be a film at all, but was initiated as part of a series of formal studies dealing with light and monochrome, using a camera with a lens covered with a sheet of white paper. When the artist took this camera onto the streets of Tunis, passers-by stopped him to inquire about this strange device. On the film’s soundtrack, we hear a man asking, “What is the point of this; what message are you trying to convey?”, to which the artist responds that he has chosen to put his confidence in the wind. We hear a self-proclaimed cinephile admitting that the meaning of this experiment surpasses him, while at the same time avowing his trust in the capacity of images to “provoke discussion”. Surprisingly, for all the opacity and uncertainty it evokes, the paper covering the camera’s eye seems to invite an upsurge of curiosity and exchange. This explains the title of the film. The screen becomes the Foyer, as artist Ismaïl Bahri suggests, where varying projections meet, but also a place of divergence amongst this community of onlookers.

Is this not also a potential definition of cinema itself? Can we think of cinema as a gathering place that gives rise to the sharing of diverse experiences? After all, doesn’t the game of appearances that unfolds before us — wavering hesitantly between the expectation of a message to decipher and a trust in “the wind blowing where it will” — open up a multiplicity of different relations, interpretations and translations? We consider this question one of the main challenges of this year’s 16th edition of the Courtisane festival. And yet, the ambition to create an accommodating foyer finds itself counterbalanced by a second challenge that is equally dear to us, one that we find encapsulated in the title of another great film that is part of the festival program: that of non-reconciliation. Can the vast world of appearances which comprises cinema remind us that the current order of things, thriving on sentiments of fear and disorientation, is no more necessary or inevitable today than it was yesterday? Can its fictions and frictions participate in the search for new worlds of possibility?