08: Jean Matthee

SELECTION 2017

A dialogue between new audiovisual works, older or rediscovered films and videos by artists and filmmakers who work in the expanded field of moving image practice.

_______________

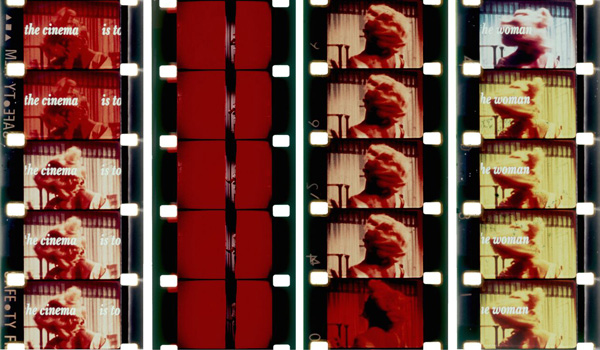

Jean Matthee was born in South Africa, where she was part of an activist film collective until the Secret Police confiscated their films. She moved to London in 1976 and became involved with the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative (LFMC). At the Co-op, she made films from a feminist perspective with the intention of interrogating the existing structures and signifiers of narrative and avant-garde cinema. Making particular use of the Co-op’s optical and contact printer at the time, she has since continued to work in a range of media with a particular interest in un-working geographies of domination. Her work often takes the militant form of a theoretical performance. Since 1976, she has traversed London almost everyday to participate in public platforms, improvising from the floor and often speaking to danger. Matthee’s 16mm films remained largely unseen for three decades until last year’s celebrations of the LFMC’s 50th anniversary. They have since been screened at Tate Modern, Anthology Film Archives and the BFI. This rare presentation at Courtisane is Matthee’s first solo screening in Belgium.

_______________

In the presence of Jean Matthee.