Artist in focus: Kevin Jerome Everson

“My work must project and reveal the materials, procedure and process. I believe that this approach is not necessarily important to be noticeable to the viewer; it merely explains how I continue to approach the craft of art making. I firmly believe that the materials of the work must be noticeable. Procedure is the formal quality I am exploring with the work. The process is the execution of the formal quality. Once I have a grasp of procedure, the process becomes a discipline.”

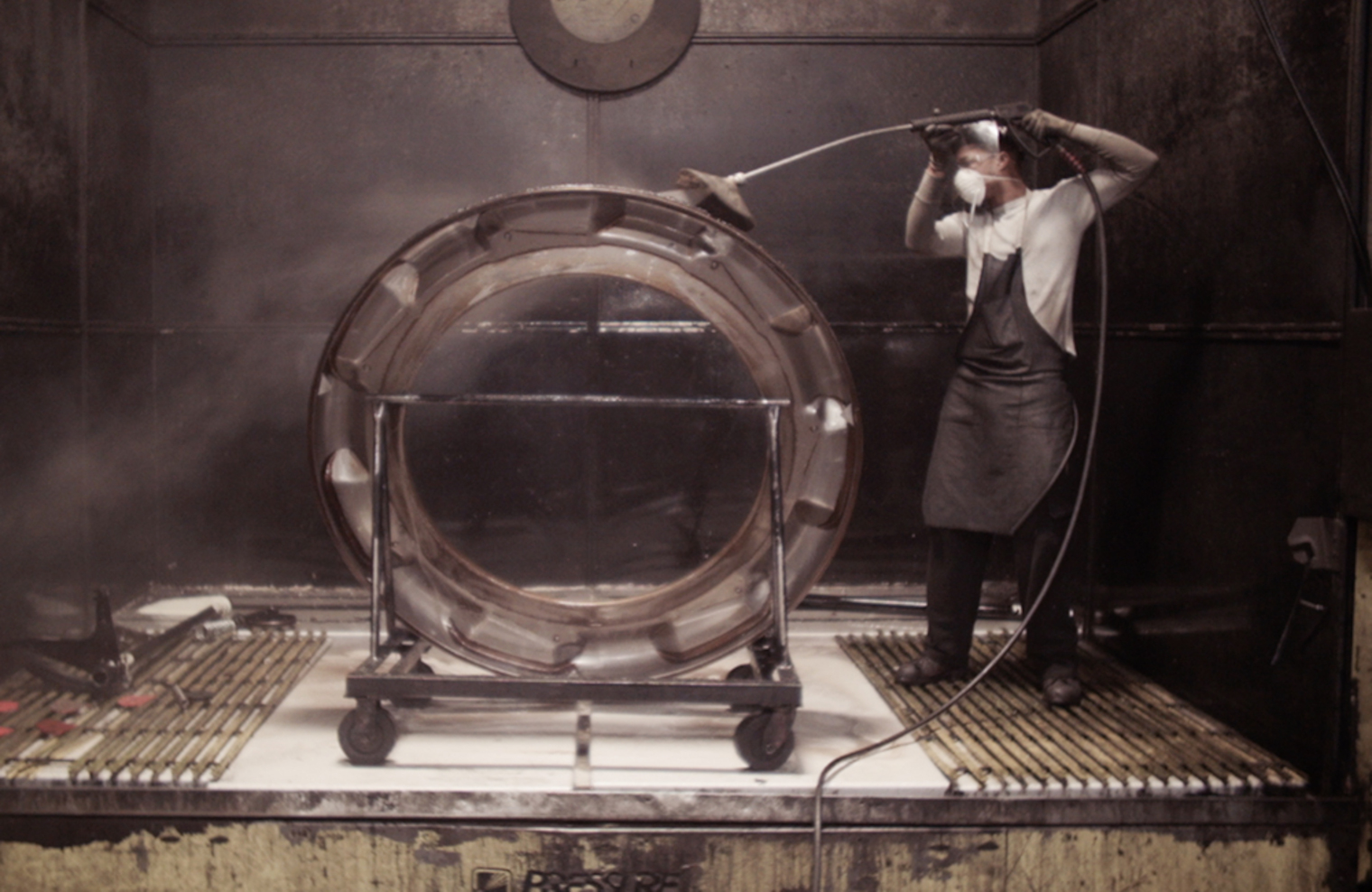

Material, procedure and process: for the artist-filmmaker Kevin Jerome Everson, these three words define the core of his artistic approach. It is with this approach, grounded in an early preference for minimalism and a background in sculpture and street photography, that he knows like no other how to evoke the poetics of the lives and experiences of working-class African-American communities. Rather than pursuing conventional realism, he elects to abstract everyday expressions into theatrical gestures and to choreograph prosaic situations as artificial compositions. Rather than seeking a classical narrative form, he tends, more and more, towards pure abstraction.

Living and teaching in Virginia but born and raised in Mansfield, Ohio, as the child of parents who came from Mississippi during the Great Migration, Everson makes films that are inextricably linked to the socio-economic conditions and histories of the Midwest and South of the United States. The place-specific conditions of work, migration, language and culture form the primary material from which he derives his subjects, whereby he pays a great deal of attention to the concrete gestures and customs that are brought about by those conditions. From Taylorian labour rituals to Spartan sports exercises, from the agility of rodeo riders to the dexterity of street magicians, Everson focuses pre-eminently on the performative qualities expressed by gestures, expressions and interactions that all too often go unnoticed and undervalued. The films not only suggest the unrelenting cycle of everyday life but also the beauty, dignity and skill that lie within it. “The people on screen are always smarter than the viewer,” he notes, “so the viewer has to catch up.”

Everson’s esteem for work and craftsmanship can also be seen in his own artistic practice and work ethic. In over twenty years, he has produced a continuously growing body of work of more than 170 short films and a dozen full-length films, which time and again stand out for their exceptional care for the specificities of place, movement, speech and form. A look at the life of black communities near Lake Erie is organized as a structural composition (Erie), a portrait of polling stations in Charlottesville, Virginia, can be experienced as a “flicker film” (Tonsler Park), a demonstration of consumer products manufactured in Mansfield, Ohio, takes on the allure of a Kerry James Marshall painting (Westinghouse). Constantly juggling between reality and artificiality, materiality and narrativity, Everson displays an ever-increasing skill in the art that was once aptly described by another craftsman as “sculpting in time”.

In collaboration with CINEMATEK,

with many thanks to Madeleine Molyneaux