Mary Helena Clark

Transparent Things: Mary Helena Clark’s films & influences /// Courtisane Preview Show

What are we seeing when watching images flickering on the screen? One could say that the cinematic experience always involves an unique play of imaginary presence (perceptual experiences, fantasies, illusions) and real absence (what is represented but not really there). The act of perception may be real, but the perceived is merely a shade, a phantom, “a hallucination that is also a fact”. It is this fundamental tension between presence and absence, actual and perceptual, the visible and the spectre of the hidden, that is at the heart of Mary Helena Clark’s work. Taking cues from the fantasy and illusion of early cinema as well as the material and formal exercises of the avant-garde, her hypnotic pieces explore cinema’s primitive magic, hurtling us down the secretive rabbit holes of the moving image. After having screened several of Mary Helena’s films in previous years, Courtisane will once again showcase her work during the coming Courtisane festival (17-21 April 2013), with the screening of her latest short film, Orpheus (outtakes). As a prologue to this year’s festival, Courtisane will present at OFFoff six films by Mary Helena Clark together with a selection of works by other filmmakers that have inspired her practice.

“Here is a selection of my films from 2008 to 2012 with work by Hans Richter, Anne McGuire, John Smith, Ernie Gehr, Anne Robertson and Saul Levine.

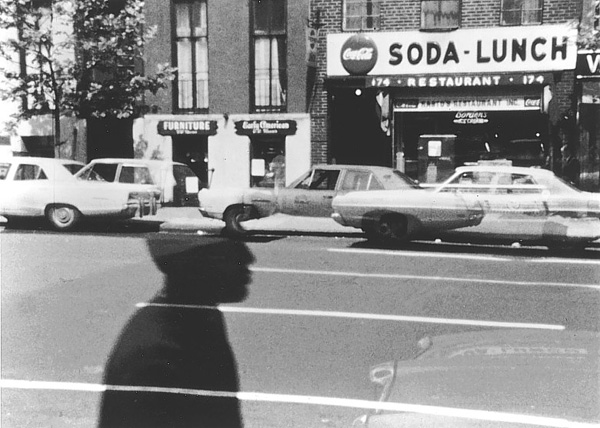

Hans Richter’s Rhythmus 21 begins the program with an exploration of constructed space. It’s a minimalist play of dimensionality, finishing with a reinstatement of the flatness of the screen space. Anne McGuire’s I Am Crazy and You’re Not Wrong still startles me with the spontaneity of her performance. You can almost hear the twists of her mind and feel the tension of the single performer on stage, threatening to turn tragic. And like McGuire, John Smith’s a major and recurring influence. Leading Light, an early work, straddles lyrical and structural modes of filmmaking, using the basic tools of exposure and sound perspective to playfully undermine the veracity of film. Also, I am partial to movies made in bedrooms. Ernie Gehr’s Untitled (1977) was described to me by Ken Eisenstein years before I ever saw it. So for me, there’s a stacking up of the told-film, the film itself, and then how that film lingers in the mind, like a play of tenses. The shifts in Gehr’s film are magical whether imagined, experienced, or remembered. Going To Work by Anne Robertson is one of her quieter pieces. This diary film observes the world with a disconnect that rings true, with a mundane profundity that can hold the viewer in bewildering stillness. Saul Levine’s Dream Story gives me goosebumps. It’s directness reminds me of why I want to make films. The title of this program is taken from a Nabokov novel of the same name. He writes, “When we concentrate on a material object, whatever its situation, the very act of attention may lead to our involuntarily sinking into the history of that object…Transparent things, through which the past shines!” ”